Transport should be at the heart of new developments – and here’s how

What is transit oriented development?

You might not instantly recognise this American term, but if you’ve been to the new development north of London’s King’s Cross station, then you’ll know what one looks like. Although still not fully completed, this once unused industrial site represents a flagship transit oriented development – the principle of putting public transport front and centre in residential and commercial developments, with the aim of maximising access by public transport, encouraging walking and cycling, and minimising the need to own and use private cars. With its shops, restaurants, offices (Google is located here), public sector organisations (Camden Council has offices here) and excellent public realm – all located within striking distance of plentiful transport options such as rail, tube, buses and active travel infrastructure like cycle superhighways, it certainly fits the bill.

Transit oriented development is not only found in large world cities. Northstowe, in Cambridgeshire, is part of the NHS Healthy New Towns programme, which aims to encourage active lifestyles and incorporate healthcare facilities into new town developments. Good public transport options are available here via the Cambridgeshire Guided Busway and the nearby Cambridge North Railway Station. And in West Yorkshire, a new railway station at Kirkstall Forge outside of Leeds, is part of a new transit oriented development which, on completion, will provide over 1,000 new homes, 300,000 square feet of office space and 100,000 square feet of retail, leisure and community facilities, including a school – all just a six minute ride train journey from the city centre.

Our new report - The place to be: How transit oriented development can support good growth in the city regions – looks at how ‘Transit oriented development’ can help meet housing demand and reduce car-based urban sprawl, and provides examples like these, and many more.

For instance, Vauban in Freiburg, Germany, is a transit oriented development which prioritises walking and cycling by having low speed limits. The area is served by a high frequency tram and all homes are within 400 meters of a tram stop. This integration of sustainable transport means that car ownership is low, at 150 cars per 1,000 residents, compared to 270 for Freiburg as a whole.

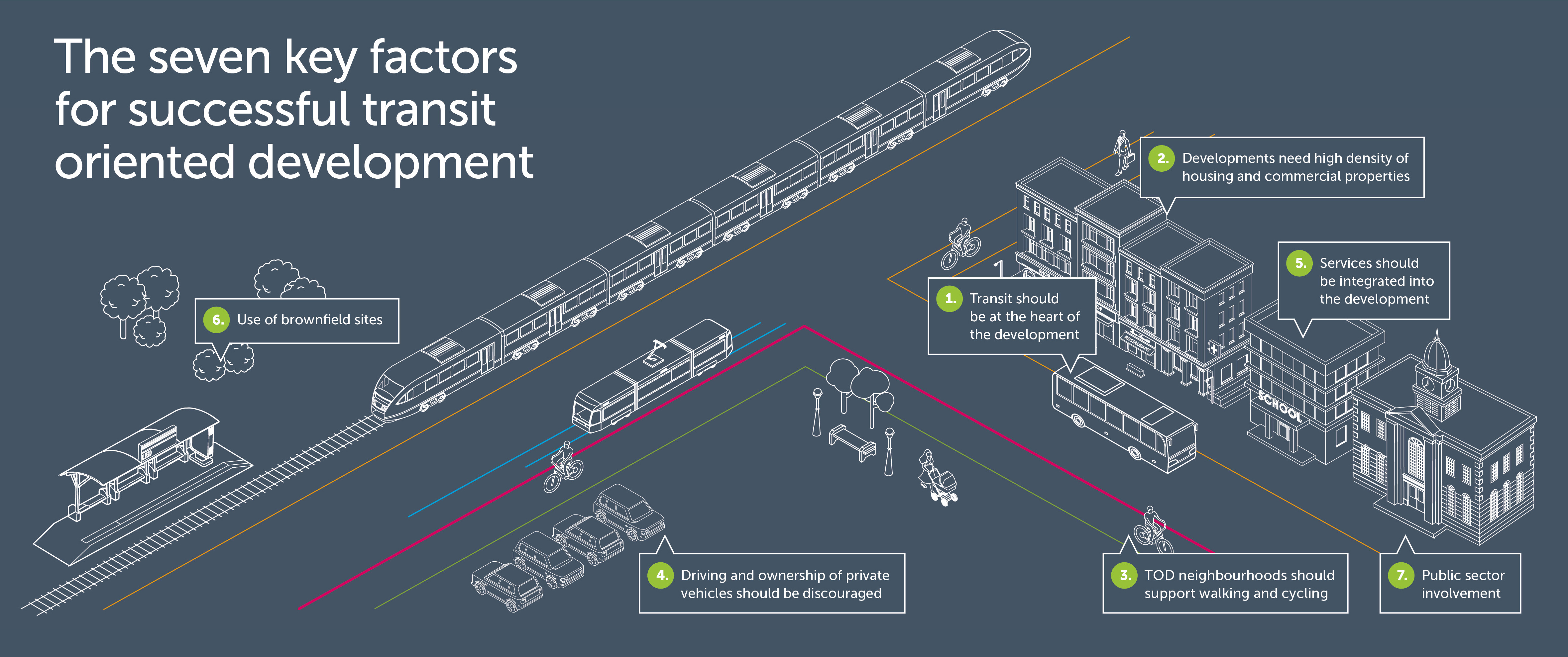

So, integrating public transport into new developments, along with providing urban realm that encourages walking and cycling, can help us move away from a car based sprawl approach to delivering new housing, one which locks residents into car-based lifestyles and exacerbates the challenges of congestion and poor air quality in our cities. We’ve identified seven key success factors for transit oriented development schemes in our new report, including: integration of public transport, support for walking and cycling and discouraging car ownership and use, high density development on brownfield sites, integration of services and the involvement of the public sector. You can see these in our new infographic below (which can be downloaded here).  But how exactly do we go about achieving such developments, and overcome some of the barriers? Our members – city region transport authorities – have an important role to play, as they are often some of the biggest land and property owners in the cities they serve. In order for them to make transit oriented developments happen, they need:

But how exactly do we go about achieving such developments, and overcome some of the barriers? Our members – city region transport authorities – have an important role to play, as they are often some of the biggest land and property owners in the cities they serve. In order for them to make transit oriented developments happen, they need:

- a national planning framework that favours transit oriented development rather than car-based low density sprawl

- a national funding framework with more options for ensuring that value uplift from new developments can be used to improve transport connectivity – like we have seen with Crossrail in London and in places like San Francisco’s Bay Area. In particular, we need a joint programme of work between city regions and national Government to examine the issues, and develop the options, on land value capture mechanisms.

- more influence over land held by agencies of national Government which would be prime sites for transit oriented development schemes. We’d like city region authorities in England to have the same veto powers over Network Rail land sales that the Scottish Government currently enjoys.

- more devolution of powers over stations where a city region transport authority has the ambition and capacity to take on those responsibilities.

- measures to improve the planning capacity of local authorities in order to respond effectively, rapidly and imaginatively to opportunities for high quality transit oriented development.

As our Chair Tobyn Hughes notes, transit oriented developments are “an idea whose time has truly come”… but if we are to embark on a new era of transit oriented developments, and realise the benefits they can bring, we must overcome these obstacles. We hope that by following these recommendations, we can usher in this new era.

Clare Linton is Researcher at Urban Transport Group (Picture top: R~P~M via Flickr)